Why I need an aftermarket motorcycle shock

Why I need an aftermarket shock?

When dealing with motorcycle suspension a few frequently asked questions include:

- Why get an aftermarket shock?

- What makes an aftermarket shock better than a production shock with the same features?

- What makes the cost of Penske, Ohlins, or Race Tech shock worth it?

- Is a re-valve and re-spring of the stock shock all that I need?

The following will address these questions and help you determine the best direction to take in terms of your suspension set up.

Why Upgrade?

Customers consider purchasing or updating their shock for a couple of reasons. They may have heard that the stock shock doesn’t work well. They could have talked to a friend that has replaced their shock, or had a stock shock re-valved. Another common reason is they may not be using the bike for its intended use i.e.; racing, track days, etc. Finally, after riding a different motorcycle then their own, many people realize their suspension just doesn’t feel as good. The one they rode may be better at handling bumps, it may steer sharper and provide better feedback with more control.

Stock/OEM Shocks

So, what is wrong with stock suspension, why do so many people claim it sucks, and what is the truth? First, let’s examine the purpose of an OEM (Original Equipment Manufacturer) production, or stock shock. Motorcycle manufactures have two main goals. One, to sell a motorcycle, and two, to make the largest possible profit from that sale. For these reasons, they want to stay competitive with rival motorcycle manufactures by providing the latest technology to come standard on their motorcycles. However, the manufacture has to make all components for their bike within a certain price point. Mass production methods help to minimize production costs, but quality of components gets limited, in part, by the quantity of parts being made. One example of this is most parts are made by cutting material off using a metal cutting tool. Over time this cutting tool will wear. As the tool wears, finished part tolerances are not exact. Because of this tolerance discrepancy in production manufacturing, the shock that comes on your motorcycle might not have the right damping rate, length, or spring rate that the engineer intended when designing the component. I frequently see this when setting up bikes trackside. After doing about 20 setups on the same year, make and model motorcycle, one starts to notice where the external adjusters provide the best feel, traction, control, etc. Sometimes, I’ll see a bike that has very little damping change or none at all when set to this desired position. This means that despite being the same part, OEM shocks will not function and perform the same. A quality aftermarket shock, manufactured with better quality control, are consistently the same at a given external adjustment position. This is due, in part, to the number of parts made in a production run by an aftermarket high performance shock manufacture without a tool change being significantly less than the stock shocks made by OEM manufactures.

Intended Shock Use

Now let’s consider intended usage. An OEM production motorcycle has to encompass a broad range of riders. Unlike with a car, a rider’s weight greatly effects the handling characteristics of a motorcycle. For example, consider a popular sports car like the BMW M3 versus the Yamaha YZF R1 motorcycle. The BMW weighs about 3500lbs. The YZF R1 weighs about 450lbs. The weight of the average American male is 176lbs. If you put this average person in the BMW, their weight is 4.78% of the GVW (gross vehicle weight). Put them on top of the Yamaha and their weight is 28.11% of the GVW. Now, what about a 210lb person? In the BMW, their weight is 5.66% of the GVW. On the R1 the rider now accounts for 31.81% of the GVW. With the BMW, there is only a 0.88% weight difference in GVW when switching from a 176lbs to 210lbs passenger. However, with the Yamaha, there is a 3.70% difference in GVW when switching to the 210lbs rider. The change in weight of a rider on a motorcycle has a larger impact on how a motorcycle needs to handle that weight.

Given that the difference in rider weight causes a difference on the suspension setup, where that weight is distributed on a bike will also affect how the bike handles. If a rider leans forward, backwards or hangs off the side of a bike, he can change the Center of Gravity (CG) location. This change in CG will cause the bike to handle differently. If a rider moves forward, the front will compress a little more, shortening trail and make the bike turn quicker. If a rider shifts their weight to the rear, the front end rises and the bike steers toward the outside of a corner. In a car, the driver basically stays in one place. Because the weight does not move around in a car, the CG is static and thus a suspension technician knows exactly where that weight will be all the way around a corner. A technician can change the setting on the car and doesn’t have to worry about the CG moving, which would affect the handling characteristics.

An aftermarket shock should be purchased with your weight and intended use in mind. This way the proper springs, damping rates, and ride heights can be taken into account to provide the best possible handling.

Shock Adjustability

Arguably the most important difference between production and aftermarket shocks is stocks shocks lack of external adjustability. Although most late model sport bikes come standard with shocks that have external adjusters, including high speed compression, low speed compression and rebound, are they really making changes to the damping? Or, by how much does one turn change? I’ve seen a lot of riders even some suspension tuners not know or address this problem. When turning a screw, how much is the damping actually changing?

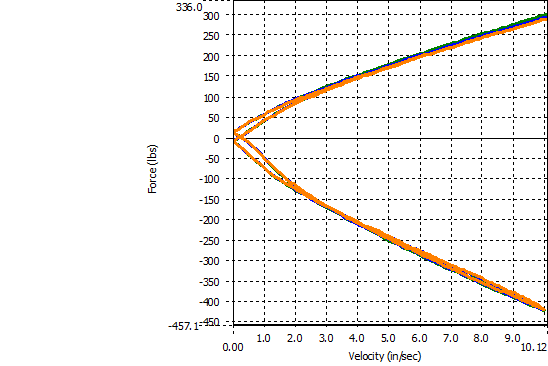

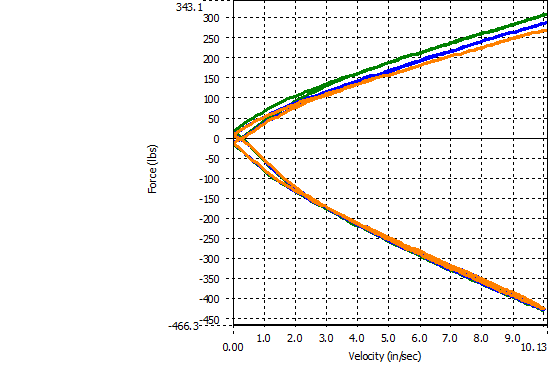

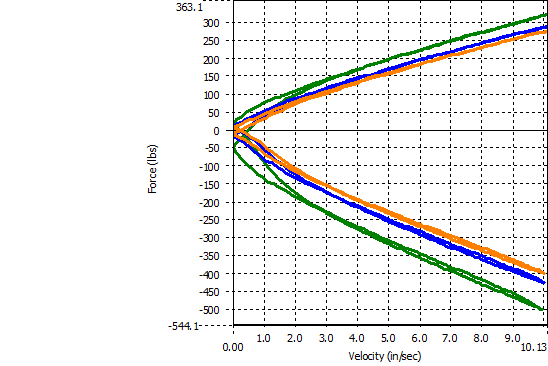

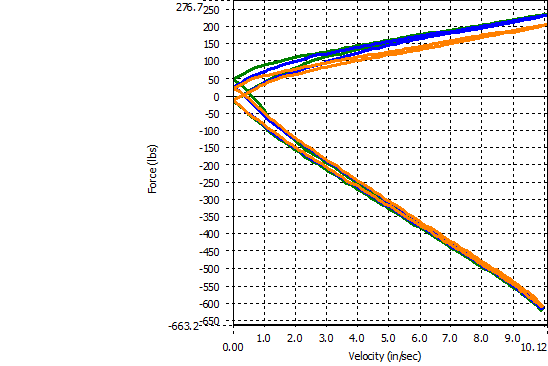

The graphs below are of a production Suzuki shock off a new 2014 motorcycle with less than 40 miles on it. They are all range tests performed on our Roehrig shock dynamometer. This dynamometer, or dyno, strokes a shock without a spring mounted and measures the amount of force it generates, over a given speed of shaft movement. The first set of graphs is the range of all three external adjustments on this Suzuki production shock. The top of the graph, positive force numbers, is damping force the shock creates when the shock is compressed. The bottom, negative force numbers, are rebound when the shock is extending. In all three test only one external adjuster is changed for the corresponding test in three positions.

- Position 1(Green) - Full hard, adjuster all the way in.

- Position 2(Blue) - Mid setting, adjuster set halfway in its adjustment range.

- Position 3 (Yellow) - Full soft, adjuster all the way out.

High Speed Compression

Low Speed Compression

Rebound

Analysis

The first big thing to notice on this production shock is that the rebound adjustments also affects compression damping. This can be corrected with a small part that Race Tech makes called a rebound separator valve. Once installed the external rebound adjuster only affects rebound damping. This is recommended on all production shock re-valves. This part may increase the compression damping and it should be installed by MRP, Race Tech or a qualified Race Tech Service Center.

Second, the high speed compression adjuster doesn’t seem to change much. Don’t take too much from this, because we only are testing this shock at a max of 10in/sec. When on a race track or the street a shock will encounter a higher velocity. The high speed adjuster may make some adjustments at a speed we can’t test on our dyno.

Third, the low speed compression adjuster, well, doesn’t have much range. It might not be noticeable if you are looking at a shock dyno graph for the first time. A low speed adjuster should effect just that, low speed movement of the shock. This production shocks low speed adjuster doesn’t do much on low speed movement, 0-3in/sec. It also changes the compression throughout the speed ranges tested. Not exactly ideal to label it a “low speed adjuster”. Most external speed range adjusters will have some crossover to other speed ranges and circuits. A performance shock will minimize this crossover.

Aftermarket Shock Adjustability

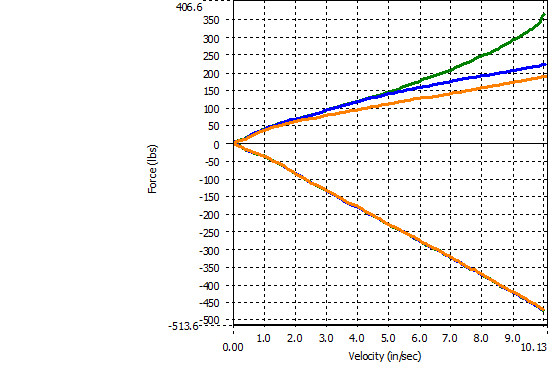

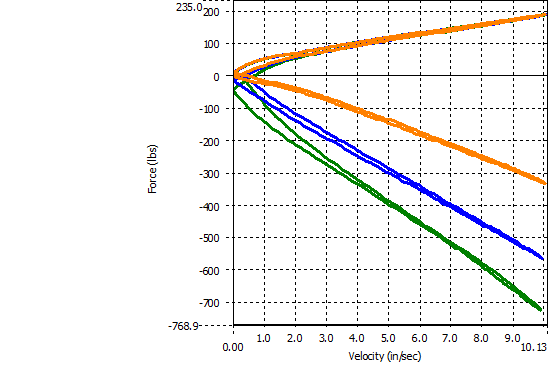

Now, let’s look at the external adjusters on a shock that we recommend often. Penske’s 8987 motorcycle shock absorber. This shock sometimes referred to as a triple clicker, because it has dampening adjustments for three ranges like the stock Suzuki shock. Below are the same test that we ran on the Suzuki production shock above.

High speed compression

Compare this high speed adjuster with the graph on the production shock and you can see right away that this shocks external adjust does what it says. There isn’t much, if any, low speed damping change. Full soft to mid settings are almost linear. Mid to full hard makes more change per click in the high speed range.

Low Speed Compression

While the low speed adjuster does affect the high speed with some crossover, most of the adjustment affect can be seen in the low speed range of 0-3 in/sec.

Rebound

Rebound stays separate compared to the production shock tested. The range of adjustability on this Penske shock is 350 lbs of force at 8 in/sec. Compare this to the production shocks 200lbs. More range in an external adjuster is a big help when tuning for different track conditions or spring changes.

Most aftermarket shocks also come with a couple other features that make setting a bike up for your riding much easier. Most will have ride height adjustability. This usually includes a nut at the bottom of the shock shaft that can be turned to increase ride height or decrease it. Making the bike handle quicker, slower, or even changing rear tire grip characteristics. A preload adjuster, to give the spring more force to handle small differences in loads, a passenger, extra gear and luggage. Most aftermarket shocks are easy to rebuild. Damping changes, spring changes and routine maintenance become quick and easy.

OEM Shock Modifications

We can re-valve and spring a production shock for your weight and riding style. We can also install a rebound separator to make the external rebound adjuster only affect rebound damping. We cannot change the range of external adjusters. (Well, we can if we design and machine a new adjuster assembly, which would most likely put your production re-valve in the aftermarket shock price range). For the price, a re-valved production is always a good option when looking to upgrade the suspension on your motorcycle. The difference, the reason the extra money for the aftermarket shock is worth it, is in the details. The range of external adjusters, the consistency of parts, purposely built for your riding, additional tuning options, and ease of maintenance. These are the reasons we recommend a customer buy an aftermarket K-tech, Penske, Ohlins, or Race Tech shock when upgrading suspension.

KM